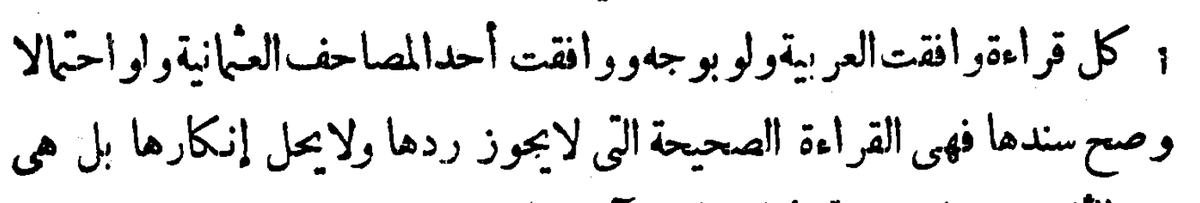

While this explicit formulation is fairly late (Ibn al-Ǧazarī dies 833/1429), it's clear that these three principles always played an important role in evaluating readings, already in the time of Ibn Mujāhid (who canonzied the first seven of the ten canonical readers).

Only the third requirement, a sound transmission, does not have any obvious deviations. But it is important to understand what a 'sound transmission' means in a reading tradition: we do *not* know the chain of transmission of every single word of every single reading.

All we have is a catalogue of who someone's main teacher's and students are. Therefore, when there is disagreement within the transmission of a tradition, we do not know how this traces back to the prophet (or, in fact, if it does at all). Let's look at a concrete example:

These three requirements were clearly important, and important early on. Exegetes clearly use forms of these requirements to evaluate specific individual readings. But it does *not* work as a requirement to distinguish between sound and šāḏḏ reading traditions!

Logically, one would think: Any reading tradition that (mostly) agrees with these three requirements is "sound" and anything that is outside is "šāḏḏ"... but surprisingly that is not at all how it works.

The sound ones definitely (generally) fit the three requirements...

The sound ones definitely (generally) fit the three requirements...

and there are plenty of šāḏḏ ones that don't. Most notably the non-canonical readings of companions frequently deviate from the rasm quite a bit more than "only a little bit", but even later readers such as Ḥamzah's main teacher al-ʾAʿmaš deviate from the rasm frequently.

But very often "šāḏḏ" readings do not contain anything that would disqualify them as being just as acceptable as the canon. This is of course clear from the fact that, e.g. Ibn Ḫālawayh still calls ʾAbū Ǧaʿfar a šaḏḏ reading, but Ibn al-Ǧazarī accepts him into the canon...

But it's not the case that *only* Ibn al-Ǧazarī's three aditional ones are "sound enough". Al-Yazīdī, ʾAbū ʿAmr's main transmitter, also had his own reading.

His ʾIsnād is obviously sound, and he only differes in the minutest of ways from his teacher.

His ʾIsnād is obviously sound, and he only differes in the minutest of ways from his teacher.

There is no obvious reason, using the 3 requirements why al-Yazīdī would be considered "šāḏḏ". Were the 5 places where he chooses to deviate from ʾAbū ʿAmr done without another ʾIsnād? Impossible to know. But that's also impossible for, e.g. al-Kisāʾī above

But we can even turn the teacher-student relation: Yaʿqūb is one of the canonical readers. His main teacher was Sallām. Sallām's reading follows the rasm, there's nothing wrong with the grammar and if his ʾIsnād isn't sound, then Yaʿqūb's wouldn't be either!

So why is Yaʿqūb's reading sound, whereas Sallām's is Šāḏḏ? Presumably this was just a popularity contest: Yaʿqūb's reading was simply transmitted more than Sallām's, and thus came to be broadly accepted. The transmission of Sallām, being more marginal, was relegated to Šāḏḏ.

So to some up: the famous "three requirements" are a useful, and indeed frequently used tool by scholars to evaluate individual specific words that may be read differently.

Using these requirements, some readings may be rejected, even when used by the now canonical readers.

Using these requirements, some readings may be rejected, even when used by the now canonical readers.

But the requirements do not manage to explain adequately at all why some reading traditions -- i.e. a fully transmitted rendition of the full Quran attributed to a historical reader -- are considered sound and which ones are considered Šāḏḏ.

@CikrikciE Of course, in New Testament studies it is of vital importance to get at what the original text of the different books of the Bible is. In part because it is such a mess. That's lower text critcism. For the Uthmanic text, there's really not much to do: the text is super stable.

@CikrikciE After reconstructing what the most likely original text is, you then proceed to ask: to what extent is this historically "reliable". Maybe that's what you mean by preservation. If you do, then yes HC is interested in it, and as am I :-)

@CikrikciE But where for the lower text criticism we are in a fantastic position for the Quran (and in a terrible position for the New Testament), that secondary question is much much harder with the Quran.

The 4 gospels give early independent accounts of the life of Jesus.

The 4 gospels give early independent accounts of the life of Jesus.

@CikrikciE With that you can use the Historical Critical method to that closer to what parts of those accounts are things the Historical Jesus actually said and did.

That's... not an option for the Quran. We have the Uthmanic text, which claims to be God's words through Muhammad.

That's... not an option for the Quran. We have the Uthmanic text, which claims to be God's words through Muhammad.

@CikrikciE There is no multiple attestation in that sense. The closest thing we get to that is:

- Medieval reports of companion codices.

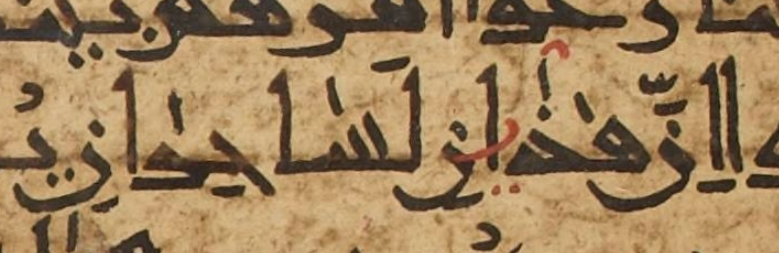

- The Sanaa Palimpsest.

Both of those are fragmentary. But both give us some confidence that a large part of the quran's contents is very early indeed.

- Medieval reports of companion codices.

- The Sanaa Palimpsest.

Both of those are fragmentary. But both give us some confidence that a large part of the quran's contents is very early indeed.

@CikrikciE But none of it confidently brings us back to the prophet. Just... very very close.

And that's where I think the question of "preservation" becomes uninteresting. Because there are just no ways to get closer to the source, and the question even becomes whether NT methods work.

And that's where I think the question of "preservation" becomes uninteresting. Because there are just no ways to get closer to the source, and the question even becomes whether NT methods work.

@CikrikciE If we are to trust the reports of the 7 ʾAḥruf (which I'm inclined to trust), it seems that in the very early period there was variation in how the Quran was recited, and that certain amount of oral variation was basically (mostly) "shut down" by the Uthmanic text.

@CikrikciE There is absolutely no way to know what the prophet originally said, and whether the Uthmanic text is the most accurate representation of that. The question in that model doesn't even make sense. It is very likely that the prophet said it in multiple ways...

@CikrikciE Every now and then with competing readings you can make an argument for one being more likely than the other, but most of the time, we simply don't know and we *certainly* don't know of the prophet taught all, some or none of them.

@CikrikciE This part of the process is mostly opaque to the historical critical method. So it's uninteresting because there is no answer to the question with the tools that we have, and it's not even clear that there could be a meaningful answer.

جاري تحميل الاقتراحات...